The spine of the book caught my eye as I sifted through a bin of sepia-tinted newspapers, teacher manuals and college course materials. I spied “A. Barton Hepburn: His Life and Service To His Time’’ and “Joseph Bucklin Bishop’’ embossed in gold lettering on a dark green cover.

My mother, Eileen, a labor and delivery nurse for 47 years at then-A. Barton Hepburn Hospital, had given the book to me. I intended to read it but tucked it in a plastic bin. Although I had forgotten about it, I simply couldn’t toss it, 20 years later, into the recycling container. My curious nature insisted that I examine the book’s contents.

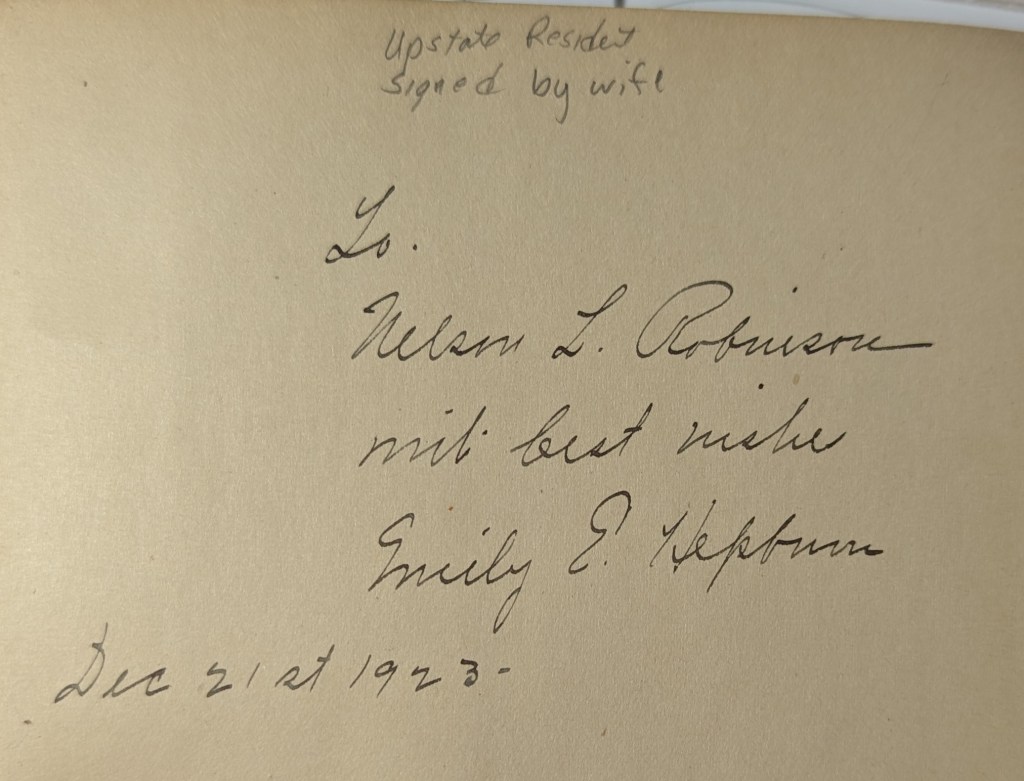

The reward was immediate. On the inside cover, the handwritten, ink inscription stated:

“To Nelson L. Robinson’’

“with best wishes’’

“Emily E. Hepburn’’

“Dec. 21st 1923’’

Someone had written, in pencil:

“Upstate Resident’’

“Signed by wife’’

This retired reporter wondered about the four names and began the goose chase. This story had elements from Scotland in the 1700s, immigration to the fledgling United States, old-money institutions, St. Lawrence University and North Country villages.

A. Barton Hepburn was easy to pursue. The namesake of the hospital, founded in 1885 as Ogdensburg City Hospital and Orphan Asylum, was a community institution managed by the Grey Nuns Sisters of Charity. It was renamed in 1918 to honor Hepburn’s donations. In 2000, the name was changed to Claxton-Hepburn Medical Center to acknowledge a sizable gift from Dr. E. Garfield Claxton.

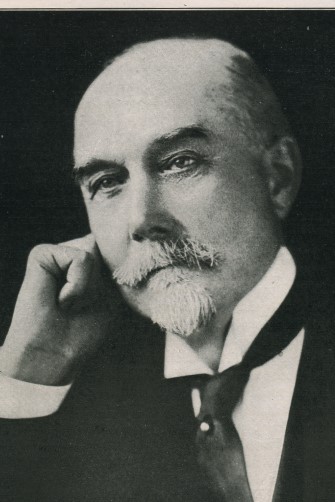

Hepburn had an extensive North Country legacy. The last of four boys, he was christened Barton upon his birth in Colton on July 24, 1846, but added the name Alonzo and insisted on the abbreviation. Upon graduation from Middlebury College, he returned to Canton to become a math professor at St. Lawrence in 1871, then became principal of Ogdensburg Educational Institute. He served in the state Assembly and built his reputation by investigating railroads’ practices of giving rebates – smelled like kickbacks — to oil companies.

In 1880, he became superintendent of the state Banking Department and eventually president of Chase National Bank. That led him to work under two presidents – Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland. He also wrote several books about coinage and currency, finance and canals.

Joseph Bucklin Bishop began his professional writing career in the 1870s on Horace Greeley’s “New York Tribune’’ before joining the “New York Evening Post’’ in the 1880s. He wrote profiles of leading Tammany Hall figures that exposed their roles in crime and corruption in New York City politics. He joined Teddy Roosevelt’s administration as executive secretary of the Panama Canal commission, and later wrote several books about Roosevelt and the canal. It is safe to assume that Bishop, in his mid-70s, was hired by Hepburn to compile this biography.

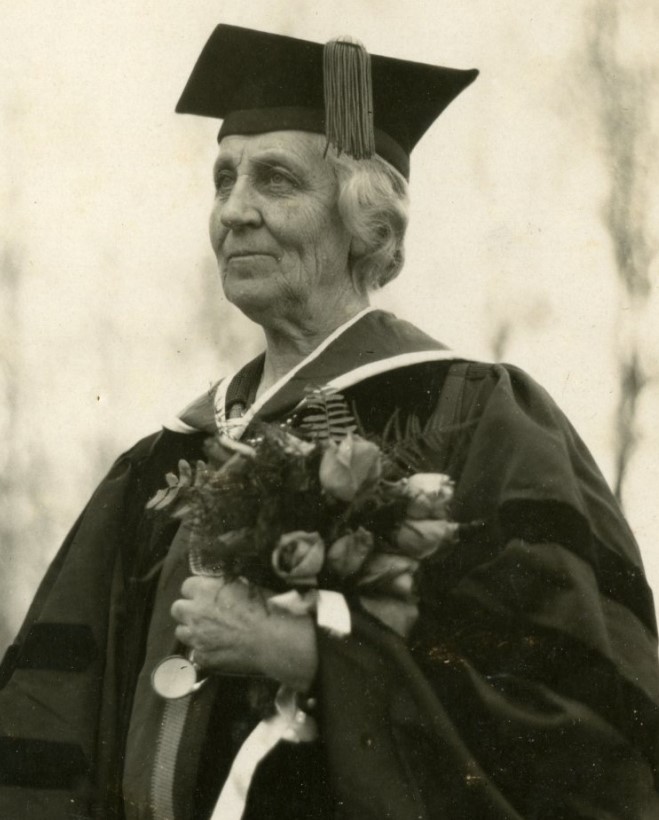

Emily E. Hepburn was Hepburn’s second wife. The “E’’ represents her maiden name, Eaton. Emily Lovisa Eaton was born in 1865 in Middlesex, Vermont, grew up on a farm, and was educated in Montpelier, then enrolled at St. Lawrence University. After graduation, at 22 years old, she married Hepburn, a 41-year-old widower with two sons, in 1887.

Nelson L. (Lemuel) Robinson, born in Morley,hailed from one of St. Lawrence County’s oldest families. He graduated from SLU in 1877, then practiced law from his Canton office. When SLU faced financial woes in 1885, Robinson organized a consortium of students, faculty and alumni. They gathered $50,000 in pledges to keep afloat the Canton university. That probably led to his friendship with Emily Hepburn.

So I had my four names figured out. Prominent writer tells philanthropist’s story, then his wife signs a copy for a SLU friend.

The Hepburn biography seemed to be a self-serving, vanity book with chapters on his family roots in Scotland, Scots-Irish generations in Londonderry, Ireland, childhood in Colton, N.Y., positions in the state legislature, career as a bank examiner and bank superintendent, and big-game hunting and salmon fishing trips. The passage that most intrigued me was Chapter 20 subtitled “Ogdensburg Hospital.’’

In summer 1916, the Ogdensburg hospital started a campaign for an enlargement and had raised about half of its $60,000 goal. After hearing of the project, Hepburn was traveling through Montreal en route to a salmon fishing excursion and invited hospital representatives to meet him. He listened, said little, indicated he would think it over during a walk, then returned to the meeting and pledged $80,000 to the building fund and a $50,000 endowment. Within days he wrote a letter from his fishing club in Gaspe, Canada, that praised the hospital and disregarded widespread anti-Catholic sentiments of the day.

“The sisters are entitled to the highest praise for their most devoted and efficient labors,’’ he wrote. “A powerful factor in giving the hospital the prestige it enjoys is the constant labor of Doctor G.C. (Grant C.) Madill, whose skill in surgery has few equals and whose quality as a public-spirited citizen has no superior.’’

The Board of Managers began construction on the addition in January 1918 and renamed the building A. Barton Hepburn Hospital. Hepburn wasn’t done. In 1921, he announced he would give the hospital 1,000 shares of Chase National Bank stock, worth approximately $345,000. By the time of his passing in 1922, he had given about $1 million to the hospital.

His generosity wasn’t limited to Ogdensburg. He gave money to build Hepburn Hall (dormitory) and Hepburn Zoo (dining hall) at Middlebury College. The term Hepburn Zoo was used because it contained several of Hepburn’s big-game hunting trophies. He also paid to construct libraries at Colton, Lisbon and Norfolk.

In the spirit of Hepburn, I should donate the book to the hospital.

Morristown native Jim Holleran is a retired teacher and sports editor from Rochester. Reach him at jimholleran29@gmail.com or view past columns under “Reflections of River Rat’’ at https://hollerangetsitwrite.com/blog/

Very interesting history. Educating and inspiring for possible donors. Think how many benefited from 1 man and many sisters and nurses. Maybe generosity is not dead.

LikeLike

Or donate to City Historian Julie Madlin at the Ogdensburg Museum.

LikeLike