Every time the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald is discussed, Kathy McSorley lives through another 15 minutes of fame, sort of a “Groundhog Day’’ movie.

TV documentary? Let’s talk with Kathy.

Another book – The Gales of November – is published? What does Kathy think?

The 50th anniversary of the Great Lakes tragedy? That’s Kathy’s family!

“I don’t see myself as a celebrity,’’ said McSorley, retired from careers as a real estate agent and administrative aide at the St. Lawrence Psychiatric Center. “I’m just proud to be a part of the legend.’’

This Monday, Nov. 10, will mark the 50th anniversary of the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald in Lake Superior. McSorley’s uncle, Ernest, was the ship’s captain, leading a crew of 28 men. They were being tossed by winds gusting to 75 miles per hour and swells reaching 25 feet when the iron-ore carrier took on water and plummeted to the lake bottom, 535 feet down. There were no survivors.

If you’re talking shipwrecks, the big three are Titanic, Lusitania and Edmund Fitzgerald. The “unsinkable’’ Titanic struck an iceberg on its maiden voyage in 1912, about 400 miles south of Newfoundland, killing more than 1,500. Americans were further horrified in May 1915 during the run-up to World War I when a German U-boat sunk the British passenger liner Lusitania off the southern coast of Ireland, killing 1,197 tourists.

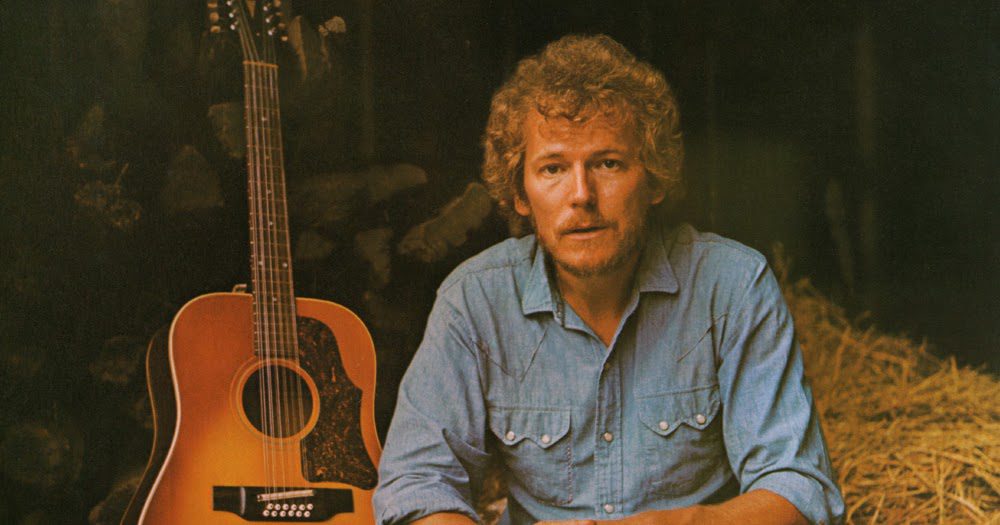

Experts figure there had been 6,000 to 10,000 shipwrecks on the Great Lakes before the Fitz sank, but its notoriety spread and endured thanks to the 1976 Gordon Lightfoot ballad “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.’’

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake, they called Gitche Gumee

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

When the skies of November turn gloomy

Lightfoot wrote the song after reading a Newsweek article that misspelled “Edmond.’’ He decided that the sailors who perished deserved a greater legacy, so he began researching books, newspapers and magazines. His haunting lyrics were recorded in Toronto and peaked at No. 2 during a 26-week run on the 1976 billboard charts in the United States. Today, the song remains a staple of oldies radio.

“I think the legend has carried on because of that song,’’ McSorley said. “Somebody will play it on the jukebox at the (Ogdensburg) Moose Club, and everyone will start singing.’’

McSorley doesn’t have a strong memory of her uncle Ernest but recalled how he and his wife would visit her parents and baby brother Mike in Heuvelton. Her father, John (Jack) drove truck for GLF (Grain, Lime and Fertilizers) that later became an Agway store. Her mother, Lillis, held jobs as a nurse and news reporter.

“The only time I got to see him much was as a child,’’ McSorley said. “I was probably not even 9 or 10.’’

“I remember that they were considered wealthy,’’ she said. “My uncle would bring my aunt (Nellie). She wore a fur coat and big hats, and it wasn’t pleasant for my mother.’’

The McSorley brothers spent their childhood in Spencerville, Ontario, but Michael and Alice Dunnery McSorley decided in 1923 to move to Mansion Avenue in Ogdensburg. Jack was 16; Ernest was 11.

As time passed, Ernest developed a love of the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes and wanted to captain a boat. After working his way up through the ranks, he became captain of the massive Fitz in 1972. Named for the president and chairman of the board of Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance, the 13,000-ton vessel was the largest ore carrier on the Great Lakes at 75 feet wide and 729 feet long.

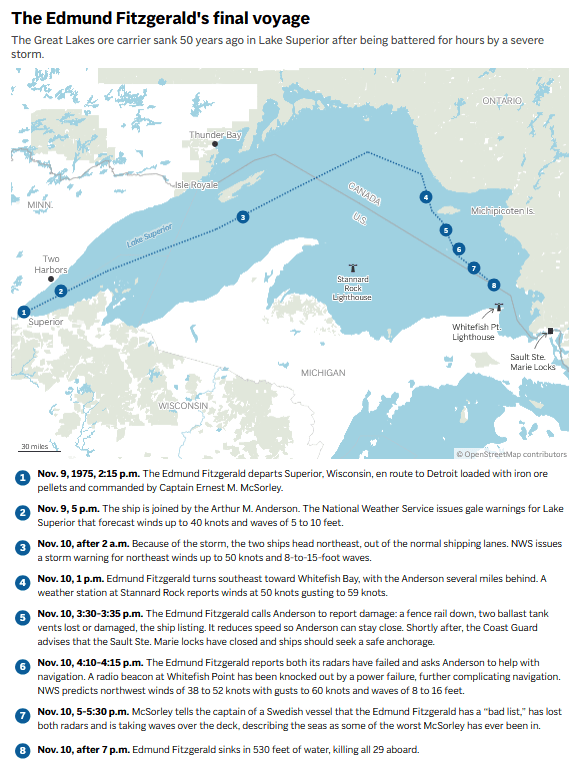

McSorley had been captain for three years, with more than 40 years of sailing experience on the Great Lakes and ocean, when the Edmund Fitzgerald left Superior, Wisconsin, about 2:30 p.m. Nov. 9, carrying 26,000 tons of iron ore pellets bound for Detroit. A weather system from the Great Plains pushed through the Great Lakes, prompting a forecast of 45 mph winds and waves of 5 to 10 feet. For safety reasons, another ship, Arthur M. Anderson, shadowed the Fitz.

The weather front intensified overnight and “the gales of November came slashin’.’’ By midday, winds rose to 65 mph with 15-foot waves when the Fitz, with two damaged hatches, headed southeast to seek anchorage in Whitefish Bay in Michigan. Around 4 p.m., the Fitz reported by radio that it had lost its two radars. Around 5:30 p.m., McSorley reported his ship had a “bad list.’’

“We are holding our own,’’ McSorley messaged the Anderson at 7:10 p.m. Those were his last recorded words. There was no distress signal. His ship was 15 miles north of Whitefish when it went down.

There were conflicting theories that leaky hatches permitted the ship to take on water, that monstrous waves snapped the ship, or that a massive wave overwhelmed the bow. Nobody knows for sure. Canadian lawmakers have preserved the site as a maritime grave.

McSorley said she visited the Edmund Fitzgerald exhibit at the Museum Ship Valley Camp in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and was presented with a painting of the ship clashing with Superior’s raging waves. It was signed by Gordon Lightfoot.

“The most remarkable part of the trip was that they gave me sonar pictures of the ship lying on the bottom, cut in two, and more pictures of divers bringing up the ship’s bell,’’ she said.

The bronze bell – 2 feet in diameter and weighing 200 pounds – was recovered in July 1995. It is rung 29 times each year at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point to commemorate the tragedy, and once more to honor all sailors lost at sea. The Mariners’ Church in Detroit holds a memorial service each year.

“I didn’t see my uncle much as a young adult, and I was 23 when the ship went down,’’ McSorley said. “But he was family. That will stay with me in my heart forever.’’

Her most moving moment remains when she stood along the shore of Whitefish Bay.

“Looking out on Lake Superior just gives you the shivers.’’

Morristown native Jim Holleran is a retired teacher and sports editor from Rochester. Reach him at jimholleran29@gmail.com or view past columns under “Reflections of River Rat’’ at https://hollerangetsitwrite.com/blog/