(An earlier version was published May 30, 2021 in Old School Sports Journal.)

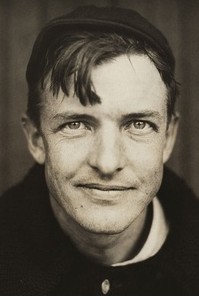

Christy Mathewson’s life had become a struggle by Memorial Day 100 years ago in Saranac Lake. He was one of the greatest pitchers in major-league baseball and later would join Walter Johnson, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner as inaugural inductees into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936.

While residents of this hilly Adirondack village were decorating graves of fallen soldiers, Mathewson was bundled in the porch chair of his cure cottage at 138 Park Avenue, trying to beat tuberculosis. He was following the only known treatment of the day – recline 8 hours a day and let the cool, fresh mountain air bathe his lungs.

It was an opponent he could not set down with his pinpoint control and deceptive screwball. The chronic coughing, fever, night sweats and weight loss overcame him five months later on Oct. 7, 1925. The New York Giants World Series hero and 373-game winner, now a shadow of his powerful 6-1, 195-pound frame, had fallen victim to the poisonous gas used in World War I, although he was far from the Western Front in France.

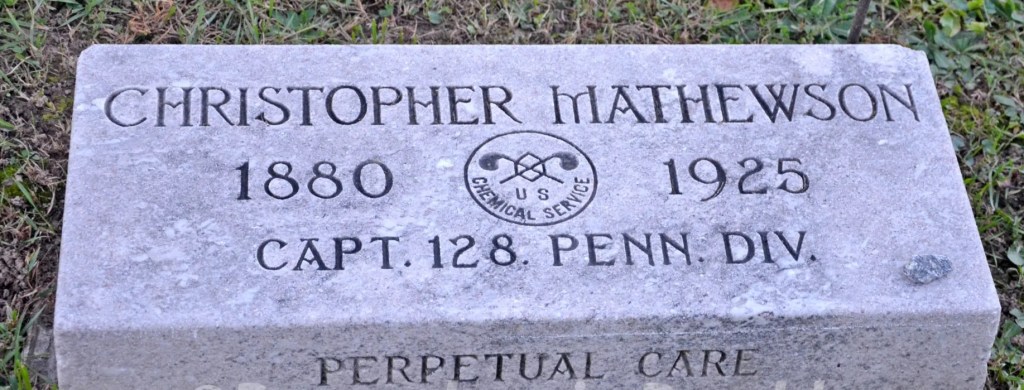

Mathewson was moved from Saranac Lake to a plot at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pa., where he had excelled at basketball and football.

In the early 1900s, Mathewson’s talent set him a tier above the boozers and womanizers who populated baseball, and his erudite nature made him a demi-god. He wrote newspaper columns ahead of big games, authored plays and children’s books, and wrote his memoir. He was dubbed “The Christian Gentleman’’ because of his kindness and a promise to his mother that he would not pitch on Sundays.

Mathewson’s trail to Saranac Lake began after he became manager of the Cincinnati Reds. World War I was raging in Europe and the Germans, French and British had incorporated a deadly new toxin into their arsenals. They were lobbing chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas on the battlefields and trenches. When the United States joined the fighting in April 1917, the top brass decided in summer 1918 to counter the gas attacks by creating a Chemical Warfare Service, regularly known as the Gas and Flame Division.

The concept was to recruit top athletes who could maneuver along battlefields and carry gas bombs and flamethrowers.

Mathewson felt compelled to join despite the wishes of his wife, Jane. While many major-leaguers were taking jobs in the defense industry and playing an abbreviated 128-game schedule on afternoons and weekends, Mathewson, then 38, resigned with 10 games left in the season and assumed the rank of U.S. Army captain.

He joined other high-powered names such as Ty Cobb, 31, who had just won his 11th batting title when he became Captain Cobb and left the Detroit Tigers for France.

Mathewson caught the flu on the transport ship and spent his first 10 days in France in the hospital. The future Hall of Famers assembled Nov. 2, 1918 in Chaumont, 120 miles south of Paris.

The group was conducting training drills with live gas in airtight chambers when Cobb and Mathewson missed a signal to strap on their masks. When the gas was released, chaos reigned. Soldiers scrambled to don masks and exit the chamber. Men screamed, arms flailed, and the gas covered the room in a shroud. Eight men were killed.

Historian John Rosengren, writing for the Baseball Hall of Fame, quoted an exchange between Mathewson and Cobb.

“Ty, I got a good dose of the stuff,” Mathewson said. “I feel terrible.”

An armistice was declared Nov. 11, 1918 before the Gas and Flame Division ever saw action. Cobb was still wheezing and coughing when his ship landed in Hoboken, N.J., on Dec. 17. He retired from baseball but felt better in spring and rejoined the Tigers.

Mathewson was hospitalized and didn’t leave France until February. He intended to resume managing the Reds in 1919, but the owner had given away his job. So Mathewson rejoined his old skipper, John McGraw, as assistant manager of the Giants. Mathewson’s lingering cough from the gas accident persisted, and that led him to Saranac Lake.

The village had evolved into a world-renowned center for lung ailments through the work of Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau. He established the Adirondack Cottage Sanitorium. Trudeau reasoned that a series of small cottages would isolate patients and prevent the airborne infections from spreading. Soon, small cottages began popping around the village.

While Mathewson was assisting McGraw with the Giants, he often shuttled between New York and Saranac Lake for stays at the Sanitorium until he retired after the 1920 season.

With a diagnosis of tuberculosis, Mathewson returned in 1921 to the village where he had a private cottage built on Park Avenue. He faced the grim prospect that he might die within six weeks.

Similar to Mathewson’s case, Word War I had caused another surge in patients. There were about 650 veterans living around Saranac Lake in 1921, prompting the Veterans Administration to open Sunmount Veterans Hospital in Tupper Lake.

The treatment seemed to work for Mathewson. He was on bed rest and several months passed before he was allowed to sit up.

Larry Brunt, writing for the Baseball Hall of Fame, recounted: “In early 1922, he was permitted to go outside and visit a local baseball game where he threw out a ceremonial pitch.’’ The press wanted updates. “I try to keep cheerful, keep my mind busy, try not to worry and I don’t kick on decisions, either by a doctor or an umpire,’’ Mathewson said.

In 1923, he organized a syndicate to buy the Boston Braves and serve as team president, but at spring training in Florida in 1925, he contracted a cold and his cough returned. He headed back to his Saranac Lake cottage and appeared to be improving as autumn arrived. But as the World Series opened in Pittsburgh on Oct. 7, the end arrived around 11 p.m.

Mathewson, 45, is reported to have said to his spouse during the week before his death, “Now Jane, I want you to go outside and have yourself a good cry. Don’t make it a long one; this can’t be helped.”

He was buried in the cemetery behind Bucknell’s Kenneth Langone Athletics and Recreation Center. The only trace you’ll find of Mathewson at the Giants’ Oracle Field in San Francisco is a retired jersey on the outfield wall with the initials “NY.’’ Players didn’t wear uniform numbers during his career.

Brunt recalled an anecdote from Mathewson’s recovery in Saranac Lake.

“… He had played catch with some boys. A reporter asked if he had any advice for them. He stopped his throwing and said they should play baseball and learn from it. Then he ended with six words that epitomize his own character: ‘Be humble and gentle and kind.’ ”

Morristown native Jim Holleran is a retired teacher and sports editor from Rochester. Reach him at jimholleran29@gmail.com or view past columns under “Reflections of River Rat’’ at https://hollerangetsitwrite.com/blog/