This sounds like the makings of a B movie.

A dashing German prisoner of war escapes from a train in snowy Quebec, makes his way across a mostly frozen St. Lawrence River, wanders through the streets of Ogdensburg, briefly becomes a local celebrity, then bolts for New York.

Too preposterous? Seems more like the work of a Hollywood scriptwriter than the imagination of a North Country novelist?

Yet the tale of Luftwaffe pilot Baron Franz von Werra is true. His arrest on a Friday night, Jan. 24, 1941, in downtown Ogdensburg gave the obscure border outpost its 15 minutes of fame, then became the basis of the 1957 film “The One That Got Away.’’ It presented von Werra as a daring, glib, blond Nazi aerial ace who annoyed his British captors with crafty escape attempts, the only World War II POW who rejoined the fighting, and his ultimate demise in a plane crash.

Long before the Ogdensburg arrest, good fortune had accompanied von Werra most of his life. It started in his childhood in Switzerland when his father, Leo, descended into bankruptcy. The von Werra children were dispersed among relatives and Franz had the good fortune to be placed in the home of a cousin’s friend, where he benefited from wealth and education.

At 22, he joined the Luftwaffe in 1936, and within two years made lieutenant. He espoused the flashy flyboy role, keeping a pet tiger as his squadron’s mascot and charming his colleagues during the Battle of Britain. He was considered an ace by 1940 with nine kills of British aircraft and was awarded the Iron Cross by Hitler.

His run of good luck ended in September 1940 when he was shot down over a farm field near Kent, England, about 40 miles southwest of London. Within days, he was caught trying to tunnel out of his POW barracks. A month later during an exercise walk, he disappeared over a stone wall, but was caught five days later. After 21 days in solitary confinement, von Werra returned to the general population. He soon slipped out of an escape tunnel and posed as a Dutch pilot at a Royal Air Force base. He climbed into the cockpit of an experimental plane and was moments from escaping when he fumbled with the controls and was arrested at gunpoint

“He was always plotting to escape,’’ Ogdensburg city historian Julie Madlin last year told WWNY in Watertown. “Whenever they had him, he was always thinking three steps ahead of them.”

The British military decided the best place to stash von Werra and discourage his spirit was to send him 3,600 miles away, to a POW camp in its Canadian commonwealth, on the north shore of Lake Superior in Ontario. He was sent by ocean transport to Halifax, Nova Scotia, then herded onto a train in Montreal, all the while plotting his escape.

“He sells his buttons on his uniform, his Iron Cross, anything he can sell on his person, and he ends up being put on this train with about 1,000 other prisoners and he gets them to help him escape off this train.’’

With guards distracted, von Werra dove through a window into a fresh snowpack, then began walking toward the St. Lawrence, figuring he would be a safe in a neutral county. (The United States would not enter WWII for another 11 months, December 1941).

Von Werra, seemingly never at a loss for words, spilled the details of his ordeal in the Canadian wilderness to Ogdensburg Journal managing editor Charles Cantwell, who published a lengthy story the next afternoon.

Von Werra said 25 prisoners were watched by three guards in each train coach. Three POWs whispered “go’’ and “stop’’ each time they felt the guards were distracted. Around 7 p.m. Thursday, von Werra made his dive into waist-deep snow. Shown a map, von Werra estimated he was about 200 miles north of Ottawa, but Cantwell narrowed it down to Mont Laurier, about 100 miles from the Canadian capital.

Von Werra walked and hitchhiked until he slept overnight at a hotel in Hull, asked a policeman for directions in downtown Ottawa, walked past the Chateau Laurier, picked up a map at a gas station and hitchhiked toward Prescott. When he spotted the river about 4:30 p.m., he figured he could walk across near Chimney Island, offshore from Johnstown, Ontario. He hid among some boathouses until 7 p.m. for cover of darkness.

When he attempted to walk across, he found open water. So he returned to the shore, dragged a boat onto the ice, and used his hands as paddles. The current kept spinning his boat, but he kept paddling until he spotted a big building (State Hospital) with bars over the windows.

Suffering from frostbite on his hands and ears and exposure to the cold, he approached two men working on a car and asked about a hotel. Allen Crites, who ran a service station on Isabella Street, gave von Werra a ride downtown. Von Werra insisted on standing on the running board, making Crites suspicious, so he notified desk sergeant Timothy O’Leary at the police station.

Officers Joseph Richer and James Deduchetto were dispatched and found von Werra at the corner of Ford and Patterson Streets. After a quick drive to the station, von Werra was held on a vagrancy charge, given a hot meal and treated by Dr. Donald Tulloch for frostbite on his hands and ears at Hepburn Hospital.

Von Werra spent the wee hours of Saturday morning chatting with Cantwell, praising Hitler’s war plans, assessing war progress, recounting his escape attempts and vowing he would return in time to wipe out England. When he was arraigned before U.S. Commissioner John Barr in the morning, charged with illegally entering the country, von Werra faced the prospect of being held until Jan. 30 for a grand jury in Albany.

His anti-Semitism was on full display.

“I would like to have an attorney if it seems necessary,’’ von Werra asked. “I would like to have the court get me a young one, and a good one.’’

“I have one in mind who would be good,’’ Barr replied, “but he is a Jew.’’

Von Werra replied curtly, “That would be impossible.’’

When attorney James Davies walked into court, Barr suggested he could be retained. The German consulate in New York was contacted and pledged the $5,000 bail.

Von Werra began chatting up locals, bought clothes, got a haircut and accepted an afternoon invitation to the Elks Club, where he chatted with locals. Most residents knew little about the Nazis’ activities in Germany and were curious about the pilot.

“He’s a charming guy. He’s funny. He’s good looking. He’s a new person in town. He’s an escaped prisoner,” Madlin said. “So, there’s kind of that ‘who’s this guy, what’s going on here.’ So, they were very curious about him. It’s like a car accident; you can’t look away.”

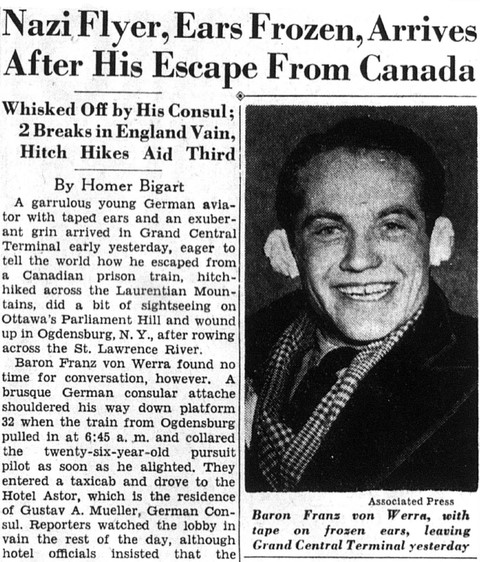

Few persons ever got to meet him. With both ears wrapped in bandages, he and his attorney boarded the 7:45 p.m. train for New York and arrived at 6:45 a.m. Sunday at Grand Central Station. He was whisked away from reporters to the Astor Hotel in Times Square. Within days, the U.S. attorney general’s office took over jurisdiction of the case.

Canadians were furious. One Prescott reader sent a note to the Journal complaining about lax treatment of the POWs by Canadian guards and questioned why Americans “sumptuously wined and dined’’ the escapee. The Ottawa Journal blamed the guards and insisted a “Nazi thug’’ should never be “coddled.’’ A Malone resident said immigration officials simply should have dropped him back on the Canadian side of the river.

While Canada was negotiating for his return, the German consulate helped von Werra escape through Mexico to Brazil, Spain, Italy and back to Germany on April 18, where he became a war hero. Hitler awarded him the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. He wrote a book, improved interrogation techniques for captured pilots, and returned to flying as a squadron leader. all while embellishing his tale and his kill count.

The Germans invaded Russia in June and von Werra’s squadron was moved to The Netherlands. On Oct. 25, his plane, presumably suffering from engine failure, crashed into the North Sea. Von Werra’s body and plane were never found and he was declared dead by the German government on Nov. 21.

Ogdensburg earned another 15 seconds of fame when the film was released in the United States in 1958.

Morristown native Jim Holleran is a retired teacher and sports editor from Rochester. Reach him at jimholleran29@gmail.com or view past columns under “Reflections of River Rat’’ at https://hollerangetsitw rite.com/blog/

Interesting story, Jim. I recently discovered that there was a POW camp in Geneseo during WW II. The county library just came into possession of a birthday poster for one of the prisoners from his soccer teammates. I was told that the inmates were parceled out to the local farms to keep them in production, since the farmers were off fighting the war.

LikeLike