When an old friend proposed we write a book on the Irish in St. Lawrence County, I jumped. Fantastic idea, I thought.

She earned a doctorate in English; I spent 30 years as a newspaper reporter and editor and authored a corporate history for my daughter’s human services agency.

The prospect of learning about my Irish brethren in the North Country was intriguing. My mother’s side hailed directly from County Clare with some German and Scots-Irish mixed in. My father’s people, I believed, left Galway, took the cheaper passage to Canada, and moved to Castleton, Vt., for quarrying jobs. Perhaps there were some New York-Vermont historical parallels I could learn.

This was going to be a rewarding retirement project. She offered an ambitious outline, we talked about shared experiences, and I began trolling around local history.

My first foray was a bellyflop. I searched for Irish Settlement roads and found three – Waddington, Canton and Heuvelton. I consulted a list of town historians, but Canton’s did not respond and there was no listing for Heuvelton and Waddington.

My friend Larry Casey of Canton suggested I check the Diocese of Ogdensburg for Catholic churches named St. Patrick’s. I found four – Brasher Falls, Chateaugay, Colton and Rossie. But historical information was sparse. Rossie’s church history stated that it was founded around 1836 by mostly Irish among the 500 residents who worked in the lead mines and iron furnaces.

It’s probable that as the Irish fled their homeland in the late 1840s during An Gorta Mor (Gaelic for The Great Hunger), many priests landed in upstate New York and pushed for missions and fledgling churches to be named St. Patrick’s in honor of the patron saint of their homeland. The congregations, however, were populated, even dominated, by the French.

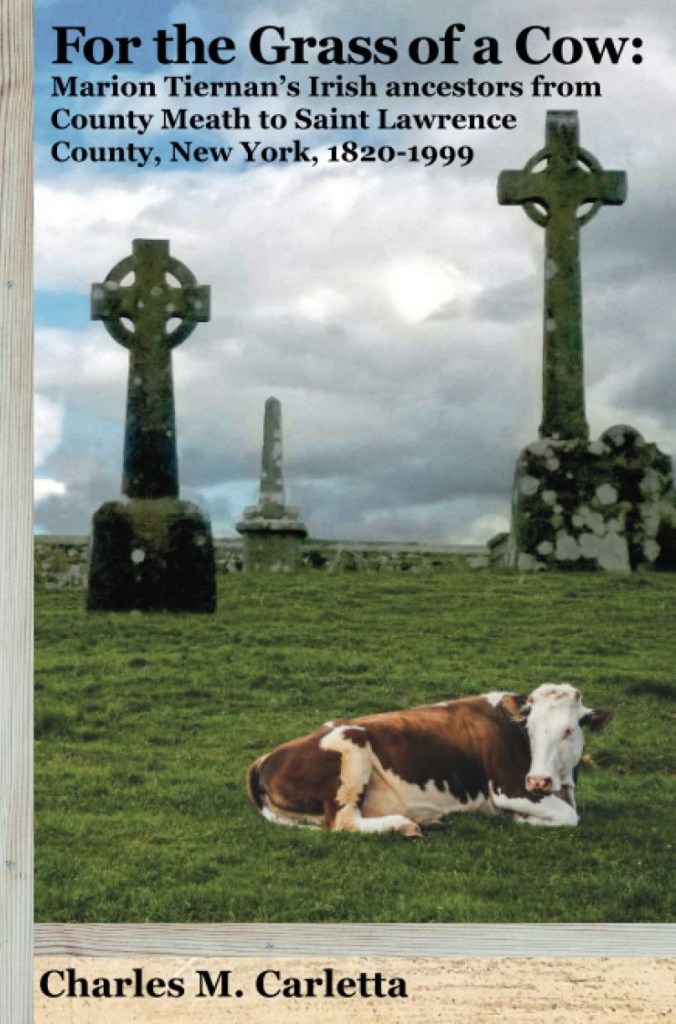

I glanced at a book “For the Grass of a Cow’’ by a retired professor from Maui College in Hawaii, Charles M. Carletta. He traced his family history from County Meath to the Waddington/Madrid area, but it was more focused on family geneaology than St. Lawrence County history.

More and more, this project was becoming more difficult. I was looking for low-hanging fruit, but there weren’t a lot of fruit trees within reach of my computer. It wasn’t impossible, mind you, but it would require poring through church and census records, perhaps going town by town to explore historical records, and interviewing hundreds of families to find people and ancestors with compelling stories. Genealogical records show the county is almost 19 percent Irish, but except for some old-time basketball coaches like Holleran, Hourihan and Merna, they all seem to be hiding.

I realized to make progress, I’d need to win the lottery, spend a great deal of time up North, commit a ton of cash for hotel rooms, and divorce myself from all the commitments to family, friends, our house, parish council, golf and basketball routines and a few donut shops. It wasn’t going to happen.

When I chatted about possible publishing options with former Ogdensburg Journal editor, Jim Reagan, now a county legislator, he led me to the most intriguing story about the Irish in St. Lawrence County – the Fenians (fee-knee-ans).

During 1845-52, at least two million Irish bolted the country searching for food and jobs. The airborne spores of a fungus had turned the prized white potatoes — principal food source for Irish peasants – into black, decaying lumps unfit for consumption.

English landlords had callously exported record amounts of grain and livestock from the island nation while the English government declined to provide any food relief, holding that the Irish would become welfare dependent. As a result, more than one million Irish died of starvation.

Many Irish fled to America’s Eastern seaboard, principally New York, and served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Anti-British sentiment continued to percolate over the years until the South capitulated at Appomattox, Va., in April 1865.

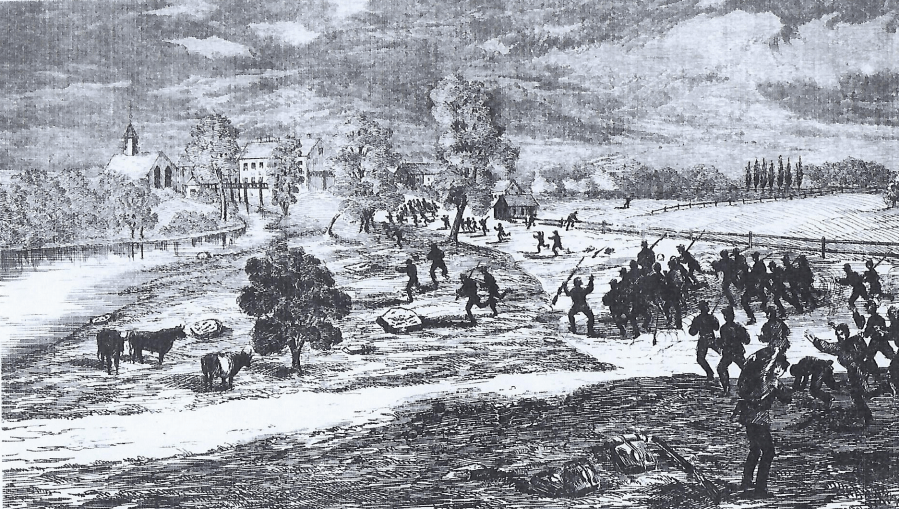

Veteran Irish soldiers found a harbor for their hatred of the English in the Fenian Brotherhood, founded in 1858 by John O’Mahony and Michael Doheny. After the war, the Fenians hatched a plan to stockpile weapons along the border, attack British forts, seize railroads and overrun small cities in Canada. The Fenians intended to swap our neighboring country for Ireland’s independence.

The first attack occurred on June 1, 1866, when an Army veteran, John O’Neill guided 600 men across the Niagara River in Buffalo, briefly held Fort Erie, but fled back across to the American side on June 3 when an overwhelming Canadian force arrived.

O’Neill resurfaced in 1870 at the Battle of Trout River, about 12 miles north of Malone near Huntingdon, Quebec. He led a skirmish with Canadian infantrymen on May 27, was quickly outflanked and overwhelmed, and retreated back across the land border where he was arrested by the U.S. marshal and charged with violating the neutrality laws, which forbade American citizens from attacking foreign countries. O’Neill was imprisoned but pardoned and released by President Ulysses S. Grant that October.

The Fenians staged raids in Manitoba and the Dakota territory in 1871, but the movement faded afterward.

The book project remains on my radar screen, but I bet it would be easier if I had French heritage.

Morristown native Jim Holleran is a retired teacher and sports editor from Rochester. Reach him at jimholleran29@gmail.com or view past columns under “Reflections of River Rat’’ at https://hollerangetsitwrite.com/blog/